- Home

- Walter Isaacson

Walter Isaacson Great Innovators e-book boxed set Page 38

Walter Isaacson Great Innovators e-book boxed set Read online

Page 38

But as Jobs paced back and forth across the stage, changing the overhead slides with a clicker in his hand, it was clear that he was now in charge at Apple—and was likely to remain so. He delivered a carefully crafted presentation, using no notes, on why Apple’s sales had fallen by 30% over the previous two years. “There are a lot of great people at Apple, but they’re doing the wrong things because the plan has been wrong,” he said. “I’ve found people who can’t wait to fall into line behind a good strategy, but there just hasn’t been one.” The crowd again erupted in yelps, whistles, and cheers.

As he spoke, his passion poured forth with increasing intensity, and he began saying “we” and “I”—rather than “they”—when referring to what Apple would be doing. “I think you still have to think differently to buy an Apple computer,” he said. “The people who buy them do think different. They are the creative spirits in this world, and they’re out to change the world. We make tools for those kinds of people.” When he stressed the word “we” in that sentence, he cupped his hands and tapped his fingers on his chest. And then, in his final peroration, he continued to stress the word “we” as he talked about Apple’s future. “We too are going to think differently and serve the people who have been buying our products from the beginning. Because a lot of people think they’re crazy, but in that craziness we see genius.” During the prolonged standing ovation, people looked at each other in awe, and a few wiped tears from their eyes. Jobs had made it very clear that he and the “we” of Apple were one.

The Microsoft Pact

The climax of Jobs’s August 1997 Macworld appearance was a bombshell announcement, one that made the cover of both Time and Newsweek. Near the end of his speech, he paused for a sip of water and began to talk in more subdued tones. “Apple lives in an ecosystem,” he said. “It needs help from other partners. Relationships that are destructive don’t help anybody in this industry.” For dramatic effect, he paused again, and then explained: “I’d like to announce one of our first new partnerships today, a very meaningful one, and that is one with Microsoft.” The Microsoft and Apple logos appeared together on the screen as people gasped.

Apple and Microsoft had been at war for a decade over a variety of copyright and patent issues, most notably whether Microsoft had stolen the look and feel of Apple’s graphical user interface. Just as Jobs was being eased out of Apple in 1985, John Sculley had struck a surrender deal: Microsoft could license the Apple GUI for Windows 1.0, and in return it would make Excel exclusive to the Mac for up to two years. In 1988, after Microsoft came out with Windows 2.0, Apple sued. Sculley contended that the 1985 deal did not apply to Windows 2.0 and that further refinements to Windows (such as copying Bill Atkinson’s trick of “clipping” overlapping windows) had made the infringement more blatant. By 1997 Apple had lost the case and various appeals, but remnants of the litigation and threats of new suits lingered. In addition, President Clinton’s Justice Department was preparing a massive antitrust case against Microsoft. Jobs invited the lead prosecutor, Joel Klein, to Palo Alto. Don’t worry about extracting a huge remedy against Microsoft, Jobs told him over coffee. Instead simply keep them tied up in litigation. That would allow Apple the opportunity, Jobs explained, to “make an end run” around Microsoft and start offering competing products.

Under Amelio, the showdown had become explosive. Microsoft refused to commit to developing Word and Excel for future Macintosh operating systems, which could have destroyed Apple. In defense of Bill Gates, he was not simply being vindictive. It was understandable that he was reluctant to commit to developing for a future Macintosh operating system when no one, including the ever-changing leadership at Apple, seemed to know what that new operating system would be. Right after Apple bought NeXT, Amelio and Jobs flew together to visit Microsoft, but Gates had trouble figuring out which of them was in charge. A few days later he called Jobs privately. “Hey, what the fuck, am I supposed to put my applications on the NeXT OS?” Gates asked. Jobs responded by “making smart-ass remarks about Gil,” Gates recalled, and suggesting that the situation would soon be clarified.

When the leadership issue was partly resolved by Amelio’s ouster, one of Jobs’s first phone calls was to Gates. Jobs recalled:

I called up Bill and said, “I’m going to turn this thing around.” Bill always had a soft spot for Apple. We got him into the application software business. The first Microsoft apps were Excel and Word for the Mac. So I called him and said, “I need help.” Microsoft was walking over Apple’s patents. I said, “If we kept up our lawsuits, a few years from now we could win a billion-dollar patent suit. You know it, and I know it. But Apple’s not going to survive that long if we’re at war. I know that. So let’s figure out how to settle this right away. All I need is a commitment that Microsoft will keep developing for the Mac and an investment by Microsoft in Apple so it has a stake in our success.”

When I recounted to him what Jobs said, Gates agreed it was accurate. “We had a group of people who liked working on the Mac stuff, and we liked the Mac,” Gates recalled. He had been negotiating with Amelio for six months, and the proposals kept getting longer and more complicated. “So Steve comes in and says, ‘Hey, that deal is too complicated. What I want is a simple deal. I want the commitment and I want an investment.’ And so we put that together in just four weeks.”

Gates and his chief financial officer, Greg Maffei, made the trip to Palo Alto to work out the framework for a deal, and then Maffei returned alone the following Sunday to work on the details. When he arrived at Jobs’s home, Jobs grabbed two bottles of water out of the refrigerator and took Maffei for a walk around the Palo Alto neighborhood. Both men wore shorts, and Jobs walked barefoot. As they sat in front of a Baptist church, Jobs cut to the core issues. “These are the things we care about,” he said. “A commitment to make software for the Mac and an investment.”

Although the negotiations went quickly, the final details were not finished until hours before Jobs’s Macworld speech in Boston. He was rehearsing at the Park Plaza Castle when his cell phone rang. “Hi, Bill,” he said as his words echoed through the old hall. Then he walked to a corner and spoke in a soft tone so others couldn’t hear. The call lasted an hour. Finally, the remaining deal points were resolved. “Bill, thank you for your support of this company,” Jobs said as he crouched in his shorts. “I think the world’s a better place for it.”

During his Macworld keynote address, Jobs walked through the details of the Microsoft deal. At first there were groans and hisses from the faithful. Particularly galling was Jobs’s announcement that, as part of the peace pact, “Apple has decided to make Internet Explorer its default browser on the Macintosh.” The audience erupted in boos, and Jobs quickly added, “Since we believe in choice, we’re going to be shipping other Internet browsers, as well, and the user can, of course, change their default should they choose to.” There were some laughs and scattered applause. The audience was beginning to come around, especially when he announced that Microsoft would be investing $150 million in Apple and getting nonvoting shares.

But the mellower mood was shattered for a moment when Jobs made one of the few visual and public relations gaffes of his onstage career. “I happen to have a special guest with me today via satellite downlink,” he said, and suddenly Bill Gates’s face appeared on the huge screen looming over Jobs and the auditorium. There was a thin smile on Gates’s face that flirted with being a smirk. The audience gasped in horror, followed by some boos and catcalls. The scene was such a brutal echo of the 1984 Big Brother ad that you half expected (and hoped?) that an athletic woman would suddenly come running down the aisle and vaporize the screenshot with a well-thrown hammer.

But it was all for real, and Gates, unaware of the jeering, began speaking on the satellite link from Microsoft headquarters. “Some of the most exciting work that I’ve done in my career has been the work that I’ve done with Steve on the Macintosh,” he intoned in his high-pitched singsong. As he wen

t on to tout the new version of Microsoft Office that was being made for the Macintosh, the audience quieted down and then slowly seemed to accept the new world order. Gates even was able to rouse some applause when he said that the new Mac versions of Word and Excel would be “in many ways more advanced than what we’ve done on the Windows platform.”

Jobs realized that the image of Gates looming over him and the audience was a mistake. “I wanted him to come to Boston,” Jobs later said. “That was my worst and stupidest staging event ever. It was bad because it made me look small, and Apple look small, and as if everything was in Bill’s hands.” Gates likewise was embarrassed when he saw the videotape of the event. “I didn’t know that my face was going to be blown up to looming proportions,” he said.

Jobs tried to reassure the audience with an impromptu sermon. “If we want to move forward and see Apple healthy again, we have to let go of a few things here,” he told the audience. “We have to let go of this notion that for Apple to win Microsoft has to lose. . . . I think if we want Microsoft Office on the Mac, we better treat the company that puts it out with a little bit of gratitude.”

The Microsoft announcement, along with Jobs’s passionate reengagement with the company, provided a much-needed jolt for Apple. By the end of the day, its stock had skyrocketed $6.56, or 33%, to close at $26.31, twice the price of the day Amelio resigned. The one-day jump added $830 million to Apple’s stock market capitalization. The company was back from the edge of the grave.

CHAPTER TWENTY-FIVE

THINK DIFFERENT

Jobs as iCEO

Enlisting Picasso

Here’s to the Crazy Ones

Lee Clow, the creative director at Chiat/Day who had done the great “1984” ad for the launch of the Macintosh, was driving in Los Angeles in early July 1997 when his car phone rang. It was Jobs. “Hi, Lee, this is Steve,” he said. “Guess what? Amelio just resigned. Can you come up here?”

Apple was going through a review to select a new agency, and Jobs was not impressed by what he had seen. So he wanted Clow and his firm, by then called TBWAChiatDay, to compete for the business. “We have to prove that Apple is still alive,” Jobs said, “and that it still stands for something special.”

Clow said that he didn’t pitch for accounts. “You know our work,” he said. But Jobs begged him. It would be hard to reject all the others that were making pitches, including BBDO and Arnold Worldwide, and bring back “an old crony,” as Jobs put it. Clow agreed to fly up to Cupertino with something they could show. Recounting the scene years later, Jobs started to cry.

This chokes me up, this really chokes me up. It was so clear that Lee loved Apple so much. Here was the best guy in advertising. And he hadn’t pitched in ten years. Yet here he was, and he was pitching his heart out, because he loved Apple as much as we did. He and his team had come up with this brilliant idea, “Think Different.” And it was ten times better than anything the other agencies showed. It choked me up, and it still makes me cry to think about it, both the fact that Lee cared so much and also how brilliant his “Think Different” idea was. Every once in a while, I find myself in the presence of purity—purity of spirit and love—and I always cry. It always just reaches in and grabs me. That was one of those moments. There was a purity about that I will never forget. I cried in my office as he was showing me the idea, and I still cry when I think about it.

Jobs and Clow agreed that Apple was one of the great brands of the world, probably in the top five based on emotional appeal, but they needed to remind folks what was distinctive about it. So they wanted a brand image campaign, not a set of advertisements featuring products. It was designed to celebrate not what the computers could do, but what creative people could do with the computers. “This wasn’t about processor speed or memory,” Jobs recalled. “It was about creativity.” It was directed not only at potential customers, but also at Apple’s own employees: “We at Apple had forgotten who we were. One way to remember who you are is to remember who your heroes are. That was the genesis of that campaign.”

Clow and his team tried a variety of approaches that praised the “crazy ones” who “think different.” They did one video with the Seal song “Crazy” (“We’re never gonna survive unless we get a little crazy”), but couldn’t get the rights to it. Then they tried versions using a recording of Robert Frost reading “The Road Not Taken” and of Robin Williams’s speeches from Dead Poets Society. Eventually they decided they needed to write their own text; their draft began, “Here’s to the crazy ones.”

Jobs was as demanding as ever. When Clow’s team flew up with a version of the text, he exploded at the young copywriter. “This is shit!” he yelled. “It’s advertising agency shit and I hate it.” It was the first time the young copywriter had met Jobs, and he stood there mute. He never went back. But those who could stand up to Jobs, including Clow and his teammates Ken Segall and Craig Tanimoto, were able to work with him to create a tone poem that he liked. In its original sixty-second version it read:

Here’s to the crazy ones. The misfits. The rebels. The troublemakers. The round pegs in the square holes. The ones who see things differently. They’re not fond of rules. And they have no respect for the status quo. You can quote them, disagree with them, glorify or vilify them. About the only thing you can’t do is ignore them. Because they change things. They push the human race forward. And while some may see them as the crazy ones, we see genius. Because the people who are crazy enough to think they can change the world are the ones who do.

Jobs, who could identify with each of those sentiments, wrote some of the lines himself, including “They push the human race forward.” By the time of the Boston Macworld in early August, they had produced a rough version. They agreed it was not ready, but Jobs used the concepts, and the “think different” phrase, in his keynote speech there. “There’s a germ of a brilliant idea there,” he said at the time. “Apple is about people who think outside the box, who want to use computers to help them change the world.”

They debated the grammatical issue: If “different” was supposed to modify the verb “think,” it should be an adverb, as in “think differently.” But Jobs insisted that he wanted “different” to be used as a noun, as in “think victory” or “think beauty.” Also, it echoed colloquial use, as in “think big.” Jobs later explained, “We discussed whether it was correct before we ran it. It’s grammatical, if you think about what we’re trying to say. It’s not think the same, it’s think different. Think a little different, think a lot different, think different. ‘Think differently’ wouldn’t hit the meaning for me.”

In order to evoke the spirit of Dead Poets Society, Clow and Jobs wanted to get Robin Williams to read the narration. His agent said that Williams didn’t do ads, so Jobs tried to call him directly. He got through to Williams’s wife, who would not let him talk to the actor because she knew how persuasive he could be. They also considered Maya Angelou and Tom Hanks. At a fund-raising dinner featuring Bill Clinton that fall, Jobs pulled the president aside and asked him to telephone Hanks to talk him into it, but the president pocket-vetoed the request. They ended up with Richard Dreyfuss, who was a dedicated Apple fan.

In addition to the television commercials, they created one of the most memorable print campaigns in history. Each ad featured a black-and-white portrait of an iconic historical figure with just the Apple logo and the words “Think Different” in the corner. Making it particularly engaging was that the faces were not captioned. Some of them—Einstein, Gandhi, Lennon, Dylan, Picasso, Edison, Chaplin, King—were easy to identify. But others caused people to pause, puzzle, and maybe ask a friend to put a name to the face: Martha Graham, Ansel Adams, Richard Feynman, Maria Callas, Frank Lloyd Wright, James Watson, Amelia Earhart.

Most were Jobs’s personal heroes. They tended to be creative people who had taken risks, defied failure, and bet their career on doing things in a different way. A photography buff, he became involved in making sure they

had the perfect iconic portraits. “This is not the right picture of Gandhi,” he erupted to Clow at one point. Clow explained that the famous Margaret Bourke-White photograph of Gandhi at the spinning wheel was owned by Time-Life Pictures and was not available for commercial use. So Jobs called Norman Pearlstine, the editor in chief of Time Inc., and badgered him into making an exception. He called Eunice Shriver to convince her family to release a picture that he loved, of her brother Bobby Kennedy touring Appalachia, and he talked to Jim Henson’s children personally to get the right shot of the late Muppeteer.

He likewise called Yoko Ono for a picture of her late husband, John Lennon. She sent him one, but it was not Jobs’s favorite. “Before it ran, I was in New York, and I went to this small Japanese restaurant that I love, and let her know I would be there,” he recalled. When he arrived, she came over to his table. “This is a better one,” she said, handing him an envelope. “I thought I would see you, so I had this with me.” It was the classic photo of her and John in bed together, holding flowers, and it was the one that Apple ended up using. “I can see why John fell in love with her,” Jobs recalled.

The narration by Richard Dreyfuss worked well, but Lee Clow had another idea. What if Jobs did the voice-over himself? “You really believe this,” Clow told him. “You should do it.” So Jobs sat in a studio, did a few takes, and soon produced a voice track that everyone liked. The idea was that, if they used it, they would not tell people who was speaking the words, just as they didn’t caption the iconic pictures. Eventually people would figure out it was Jobs. “This will be really powerful to have it in your voice,” Clow argued. “It will be a way to reclaim the brand.”

Benjamin Franklin: An American Life

Benjamin Franklin: An American Life Einstein: His Life and Universe

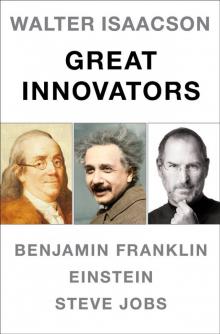

Einstein: His Life and Universe Walter Isaacson Great Innovators e-book boxed set

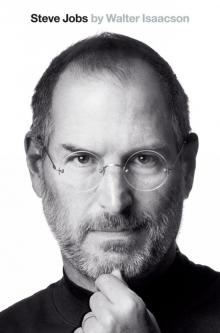

Walter Isaacson Great Innovators e-book boxed set Steve Jobs

Steve Jobs The Innovators

The Innovators A Benjamin Franklin Reader

A Benjamin Franklin Reader