- Home

- Walter Isaacson

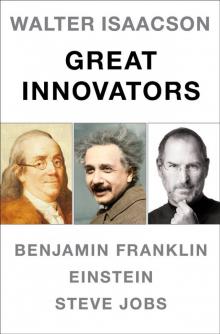

Walter Isaacson Great Innovators e-book boxed set Page 11

Walter Isaacson Great Innovators e-book boxed set Read online

Page 11

Markkula would become a father figure to Jobs. Like Jobs’s adoptive father, he would indulge Jobs’s strong will, and like his biological father, he would end up abandoning him. “Markkula was as much a father-son relationship as Steve ever had,” said the venture capitalist Arthur Rock. He began to teach Jobs about marketing and sales. “Mike really took me under his wing,” Jobs recalled. “His values were much aligned with mine. He emphasized that you should never start a company with the goal of getting rich. Your goal should be making something you believe in and making a company that will last.”

Markkula wrote his principles in a one-page paper titled “The Apple Marketing Philosophy” that stressed three points. The first was empathy, an intimate connection with the feelings of the customer: “We will truly understand their needs better than any other company.” The second was focus: “In order to do a good job of those things that we decide to do, we must eliminate all of the unimportant opportunities.” The third and equally important principle, awkwardly named, was impute. It emphasized that people form an opinion about a company or product based on the signals that it conveys. “People DO judge a book by its cover,” he wrote. “We may have the best product, the highest quality, the most useful software etc.; if we present them in a slipshod manner, they will be perceived as slipshod; if we present them in a creative, professional manner, we will impute the desired qualities.”

For the rest of his career, Jobs would understand the needs and desires of customers better than any other business leader, he would focus on a handful of core products, and he would care, sometimes obsessively, about marketing and image and even the details of packaging. “When you open the box of an iPhone or iPad, we want that tactile experience to set the tone for how you perceive the product,” he said. “Mike taught me that.”

Regis McKenna

The first step in this process was convincing the Valley’s premier publicist, Regis McKenna, to take on Apple as a client. McKenna was from a large working-class Pittsburgh family, and bred into his bones was a steeliness that he cloaked with charm. A college dropout, he had worked for Fairchild and National Semiconductor before starting his own PR and advertising firm. His two specialties were doling out exclusive interviews with his clients to journalists he had cultivated and coming up with memorable ad campaigns that created brand awareness for products such as microchips. One of these was a series of colorful magazine ads for Intel that featured racing cars and poker chips rather than the usual dull performance charts. These caught Jobs’s eye. He called Intel and asked who created them. “Regis McKenna,” he was told. “I asked them what Regis McKenna was,” Jobs recalled, “and they told me he was a person.” When Jobs phoned, he couldn’t get through to McKenna. Instead he was transferred to Frank Burge, an account executive, who tried to put him off. Jobs called back almost every day.

Burge finally agreed to drive out to the Jobs garage. “Holy Christ, this guy is going to be something else,” he recalled thinking. “What’s the least amount of time I can spend with this clown without being rude.” Then, when he was confronted with the unwashed and shaggy Jobs, two things hit him: “First, he was an incredibly smart young man. Second, I didn’t understand a fiftieth of what he was talking about.”

So Jobs and Wozniak were invited to have a meeting with, as his impish business cards read, “Regis McKenna, himself.” This time it was the normally shy Wozniak who became prickly. McKenna glanced at an article Wozniak was writing about Apple and suggested that it was too technical and needed to be livened up. “I don’t want any PR man touching my copy,” Wozniak snapped. McKenna suggested it was time for them to leave his office. “But Steve called me back right away and said he wanted to meet again,” McKenna recalled. “This time he came without Woz, and we hit it off.”

McKenna had his team get to work on brochures for the Apple II. The first thing they did was to replace Ron Wayne’s ornate Victorian woodcut-style logo, which ran counter to McKenna’s colorful and playful advertising style. So an art director, Rob Janoff, was assigned to create a new one. “Don’t make it cute,” Jobs ordered. Janoff came up with a simple apple shape in two versions, one whole and the other with a bite taken out of it. The first looked too much like a cherry, so Jobs chose the one with a bite. He also picked a version that was striped in six colors, with psychedelic hues sandwiched between whole-earth green and sky blue, even though that made printing the logo significantly more expensive. Atop the brochure McKenna put a maxim, often attributed to Leonardo da Vinci, that would become the defining precept of Jobs’s design philosophy: “Simplicity is the ultimate sophistication.”

The First Launch Event

The introduction of the Apple II was scheduled to coincide with the first West Coast Computer Faire, to be held in April 1977 in San Francisco, organized by a Homebrew stalwart, Jim Warren. Jobs signed Apple up for a booth as soon as he got the information packet. He wanted to secure a location right at the front of the hall as a dramatic way to launch the Apple II, and so he shocked Wozniak by paying $5,000 in advance. “Steve decided that this was our big launch,” said Wozniak. “We would show the world we had a great machine and a great company.”

It was an application of Markkula’s admonition that it was important to “impute” your greatness by making a memorable impression on people, especially when launching a new product. That was reflected in the care that Jobs took with Apple’s display area. Other exhibitors had card tables and poster board signs. Apple had a counter draped in black velvet and a large pane of backlit Plexiglas with Janoff’s new logo. They put on display the only three Apple IIs that had been finished, but empty boxes were piled up to give the impression that there were many more on hand.

Jobs was furious that the computer cases had arrived with tiny blemishes on them, so he had his handful of employees sand and polish them. The imputing even extended to gussying up Jobs and Wozniak. Markkula sent them to a San Francisco tailor for three-piece suits, which looked faintly ridiculous on them, like tuxes on teenagers. “Markkula explained how we would all have to dress up nicely, how we should appear and look, how we should act,” Wozniak recalled.

It was worth the effort. The Apple II looked solid yet friendly in its sleek beige case, unlike the intimidating metal-clad machines and naked boards on the other tables. Apple got three hundred orders at the show, and Jobs met a Japanese textile maker, Mizushima Satoshi, who became Apple’s first dealer in Japan.

The fancy clothes and Markkula’s injunctions could not, however, stop the irrepressible Wozniak from playing some practical jokes. One program that he displayed tried to guess people’s nationality from their last name and then produced the relevant ethnic jokes. He also created and distributed a hoax brochure for a new computer called the “Zaltair,” with all sorts of fake ad-copy superlatives like “Imagine a car with five wheels.” Jobs briefly fell for the joke and even took pride that the Apple II stacked up well against the Zaltair in the comparison chart. He didn’t realize who had pulled the prank until eight years later, when Woz gave him a framed copy of the brochure as a birthday gift.

Mike Scott

Apple was now a real company, with a dozen employees, a line of credit, and the daily pressures that can come from customers and suppliers. It had even moved out of the Jobses’ garage, finally, into a rented office on Stevens Creek Boulevard in Cupertino, about a mile from where Jobs and Wozniak went to high school.

Jobs did not wear his growing responsibilities gracefully. He had always been temperamental and bratty. At Atari his behavior had caused him to be banished to the night shift, but at Apple that was not possible. “He became increasingly tyrannical and sharp in his criticism,” according to Markkula. “He would tell people, ‘That design looks like shit.’” He was particularly rough on Wozniak’s young programmers, Randy Wigginton and Chris Espinosa. “Steve would come in, take a quick look at what I had done, and tell me it was shit without having any idea what it was or why I had done it,” said Wigginton, w

ho was just out of high school.

There was also the issue of his hygiene. He was still convinced, against all evidence, that his vegan diets meant that he didn’t need to use a deodorant or take regular showers. “We would have to literally put him out the door and tell him to go take a shower,” said Markkula. “At meetings we had to look at his dirty feet.” Sometimes, to relieve stress, he would soak his feet in the toilet, a practice that was not as soothing for his colleagues.

Markkula was averse to confrontation, so he decided to bring in a president, Mike Scott, to keep a tighter rein on Jobs. Markkula and Scott had joined Fairchild on the same day in 1967, had adjoining offices, and shared the same birthday, which they celebrated together each year. At their birthday lunch in February 1977, when Scott was turning thirty-two, Markkula invited him to become Apple’s new president.

On paper he looked like a great choice. He was running a manufacturing line for National Semiconductor, and he had the advantage of being a manager who fully understood engineering. In person, however, he had some quirks. He was overweight, afflicted with tics and health problems, and so tightly wound that he wandered the halls with clenched fists. He also could be argumentative. In dealing with Jobs, that could be good or bad.

Wozniak quickly embraced the idea of hiring Scott. Like Markkula, he hated dealing with the conflicts that Jobs engendered. Jobs, not surprisingly, had more conflicted emotions. “I was only twenty-two, and I knew I wasn’t ready to run a real company,” he said. “But Apple was my baby, and I didn’t want to give it up.” Relinquishing any control was agonizing to him. He wrestled with the issue over long lunches at Bob’s Big Boy hamburgers (Woz’s favorite place) and at the Good Earth restaurant (Jobs’s). He finally acquiesced, reluctantly.

Mike Scott, called “Scotty” to distinguish him from Mike Markkula, had one primary duty: managing Jobs. This was usually accomplished by Jobs’s preferred mode of meeting, which was taking a walk together. “My very first walk was to tell him to bathe more often,” Scott recalled. “He said that in exchange I had to read his fruitarian diet book and consider it as a way to lose weight.” Scott never adopted the diet or lost much weight, and Jobs made only minor modifications to his hygiene. “Steve was adamant that he bathed once a week, and that was adequate as long as he was eating a fruitarian diet.”

Jobs’s desire for control and disdain for authority was destined to be a problem with the man who was brought in to be his regent, especially when Jobs discovered that Scott was one of the only people he had yet encountered who would not bend to his will. “The question between Steve and me was who could be most stubborn, and I was pretty good at that,” Scott said. “He needed to be sat on, and he sure didn’t like that.” Jobs later said, “I never yelled at anyone more than I yelled at Scotty.”

An early showdown came over employee badge numbers. Scott assigned #1 to Wozniak and #2 to Jobs. Not surprisingly, Jobs demanded to be #1. “I wouldn’t let him have it, because that would stoke his ego even more,” said Scott. Jobs threw a tantrum, even cried. Finally, he proposed a solution. He would have badge #0. Scott relented, at least for the purpose of the badge, but the Bank of America required a positive integer for its payroll system and Jobs’s remained #2.

There was a more fundamental disagreement that went beyond personal petulance. Jay Elliot, who was hired by Jobs after a chance meeting in a restaurant, noted Jobs’s salient trait: “His obsession is a passion for the product, a passion for product perfection.” Mike Scott, on the other hand, never let a passion for the perfect take precedence over pragmatism. The design of the Apple II case was one of many examples. The Pantone company, which Apple used to specify colors for its plastic, had more than two thousand shades of beige. “None of them were good enough for Steve,” Scott marveled. “He wanted to create a different shade, and I had to stop him.” When the time came to tweak the design of the case, Jobs spent days agonizing over just how rounded the corners should be. “I didn’t care how rounded they were,” said Scott, “I just wanted it decided.” Another dispute was over engineering benches. Scott wanted a standard gray; Jobs insisted on special-order benches that were pure white. All of this finally led to a showdown in front of Markkula about whether Jobs or Scott had the power to sign purchase orders; Markkula sided with Scott. Jobs also insisted that Apple be different in how it treated customers. He wanted a one-year warranty to come with the Apple II. This flabbergasted Scott; the usual warranty was ninety days. Again Jobs dissolved into tears during one of their arguments over the issue. They walked around the parking lot to calm down, and Scott decided to relent on this one.

Wozniak began to rankle at Jobs’s style. “Steve was too tough on people. I wanted our company to feel like a family where we all had fun and shared whatever we made.” Jobs, for his part, felt that Wozniak simply would not grow up. “He was very childlike. He did a great version of BASIC, but then never could buckle down and write the floating-point BASIC we needed, so we ended up later having to make a deal with Microsoft. He was just too unfocused.”

But for the time being the personality clashes were manageable, mainly because the company was doing so well. Ben Rosen, the analyst whose newsletters shaped the opinions of the tech world, became an enthusiastic proselytizer for the Apple II. An independent developer came up with the first spreadsheet and personal finance program for personal computers, VisiCalc, and for a while it was available only on the Apple II, turning the computer into something that businesses and families could justify buying. The company began attracting influential new investors. The pioneering venture capitalist Arthur Rock had initially been unimpressed when Markkula sent Jobs to see him. “He looked as if he had just come back from seeing that guru he had in India,” Rock recalled, “and he kind of smelled that way too.” But after Rock scoped out the Apple II, he made an investment and joined the board.

The Apple II would be marketed, in various models, for the next sixteen years, with close to six million sold. More than any other machine, it launched the personal computer industry. Wozniak deserves the historic credit for the design of its awe-inspiring circuit board and related operating software, which was one of the era’s great feats of solo invention. But Jobs was the one who integrated Wozniak’s boards into a friendly package, from the power supply to the sleek case. He also created the company that sprang up around Wozniak’s machines. As Regis McKenna later said, “Woz designed a great machine, but it would be sitting in hobby shops today were it not for Steve Jobs.” Nevertheless most people considered the Apple II to be Wozniak’s creation. That would spur Jobs to pursue the next great advance, one that he could call his own.

CHAPTER SEVEN

CHRISANN AND LISA

He Who Is Abandoned . . .

Ever since they had lived together in a cabin during the summer after he graduated from high school, Chrisann Brennan had woven in and out of Jobs’s life. When he returned from India in 1974, they spent time together at Robert Friedland’s farm. “Steve invited me up there, and we were just young and easy and free,” she recalled. “There was an energy there that went to my heart.”

When they moved back to Los Altos, their relationship drifted into being, for the most part, merely friendly. He lived at home and worked at Atari; she had a small apartment and spent a lot of time at Kobun Chino’s Zen center. By early 1975 she had begun a relationship with a mutual friend, Greg Calhoun. “She was with Greg, but went back to Steve occasionally,” according to Elizabeth Holmes. “That was pretty much the way it was with all of us. We were sort of shifting back and forth; it was the seventies, after all.”

Calhoun had been at Reed with Jobs, Friedland, Kottke, and Holmes. Like the others, he became deeply involved with Eastern spirituality, dropped out of Reed, and found his way to Friedland’s farm. There he moved into an eight-by twenty-foot chicken coop that he converted into a little house by raising it onto cinderblocks and building a sleeping loft inside. In the spring of 1975 Brennan moved in with him, and the nex

t year they decided to make their own pilgrimage to India. Jobs advised Calhoun not to take Brennan with him, saying that she would interfere with his spiritual quest, but they went together anyway. “I was just so impressed by what happened to Steve on his trip to India that I wanted to go there,” she said.

Theirs was a serious trip, beginning in March 1976 and lasting almost a year. At one point they ran out of money, so Calhoun hitchhiked to Iran to teach English in Tehran. Brennan stayed in India, and when Calhoun’s teaching stint was over they hitchhiked to meet each other in the middle, in Afghanistan. The world was a very different place back then.

After a while their relationship frayed, and they returned from India separately. By the summer of 1977 Brennan had moved back to Los Altos, where she lived for a while in a tent on the grounds of Kobun Chino’s Zen center. By this time Jobs had moved out of his parents’ house and was renting a $600 per month suburban ranch house in Cupertino with Daniel Kottke. It was an odd scene of free-spirited hippie types living in a tract house they dubbed Rancho Suburbia. “It was a four-bedroom house, and we occasionally rented one of the bedrooms out to all sorts of crazy people, including a stripper for a while,” recalled Jobs. Kottke couldn’t quite figure out why Jobs had not just gotten his own house, which he could have afforded by then. “I think he just wanted to have a roommate,” Kottke speculated.

Even though her relationship with Jobs was sporadic, Brennan soon moved in as well. This made for a set of living arrangements worthy of a French farce. The house had two big bedrooms and two tiny ones. Jobs, not surprisingly, commandeered the largest of them, and Brennan (who was not really living with him) moved into the other big bedroom. “The two middle rooms were like for babies, and I didn’t want either of them, so I moved into the living room and slept on a foam pad,” said Kottke. They turned one of the small rooms into space for meditating and dropping acid, like the attic space they had used at Reed. It was filled with foam packing material from Apple boxes. “Neighborhood kids used to come over and we would toss them in it and it was great fun,” said Kottke, “but then Chrisann brought home some cats who peed in the foam, and then we had to get rid of it.”

Benjamin Franklin: An American Life

Benjamin Franklin: An American Life Einstein: His Life and Universe

Einstein: His Life and Universe Walter Isaacson Great Innovators e-book boxed set

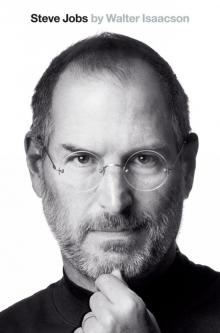

Walter Isaacson Great Innovators e-book boxed set Steve Jobs

Steve Jobs The Innovators

The Innovators A Benjamin Franklin Reader

A Benjamin Franklin Reader